History of Libraries: Library Security

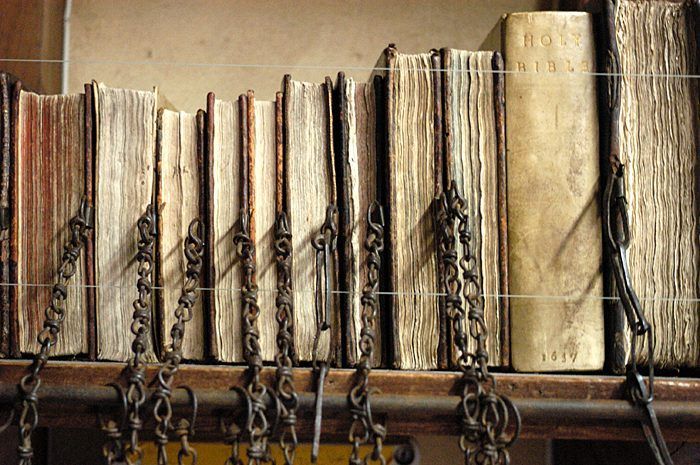

In popular culture, the image of the restricted library filled with shelves of books in chains (or hidden behind bars) can be found in Game of Thrones, Harry Potter, Dr. Strange and The Man in the High Castle, among others. In these fictional worlds, books containing important information vital to protagonists’ futures are kept under lock and key, stirring powerful emotions in audiences. Perhaps for information professionals in particular, the notion of restrictions on knowledge is shockingly incompatible with professional aims and ethics. After all, as Katie McBride writes, “Public librarians are not naturally concerned with security issues. Our philosophy centers more around granting access to resources and information than preventing it.” But what if, contrary to modern understanding of this practice, (as depicted in the pop culture references above) the chains were intended not to restrict access, but to enable it? What if as Erik Kwakkel suggests, chains demonstrate, “that the text inside the object was available in a public or semi-public place”? He continues, “In other words, chains (or traces of them) suggest how information was accessed”? Cassini, writing for Book Addiction, also promotes this angle of understanding of the practice when she writes that chaining books has other implications, stating, “To increase accessibility and circulation, monasteries began to chain individual books to sloped desks–giving a greater sense that the book was communal property rather than belonging to a particular monk.”

When considering the implications for potential meanings embedded in this practice and the ideology behind its use as a security measure, it is important to incorporate context and contemporary viewpoints. Kwakell and Cassini assert that chaining took place in public and semi-public places (such as cathedral libraries), marking the book as accessible by the public, and that chaining represents attempts not to restrict access, but to enable it. Further, that by making books available in this manner, chaining promoted an understanding of ownership as communal and use as shared. Summit observes that works such as the Bible and Foxes Acts and Monuments were often chained together, “for the reading by ordinary people at many public places including cathedrals, churches, schools, libraries, guildhalls and at least one inn (p.236).”

This conceptual understanding of the practice is buttressed by the work of Jennifer Summit (2008). Writing in “Memory’s Library: Medieval Books in Early Modern England,” she examines currents of thought regarding chained libraries and restricted access during the fifteenth century. She identifies tensions rising between an emerging literate populace in England and institutions (such as monasteries, churches and universities) who sought to protect their collections from damage and theft. She asserts that there is evidence of a growing sentiment that literacy and books should be common property (p.19). In some instances, when borrowing privileges for literate townsfolk were curtailed and stricter security enforced due to growing numbers of readers, some contemporary critics perceived libraries to be, “hoarding precious resources” (p. 18). Modern interpretations of the chained library that portray chained books as captives of selfish monks, according to Summit, “misrepresent the history of chaining… by overlooking its historical rationale, which was to make the books available to readers rather than to hoard them (215).”

Entertaining this interpretation does not demand total rejection of restriction of access as an aim of chaining books. Differing interpretations of the practice underscore the need for nuanced approaches to this topic. The history of chained libraries raises many questions, both practical and theoretical, with multiple ideological implications. Was it necessary? Why? Were all books chained, or just particular titles? What security issues existed in early libraries? What did security solutions entail? What other impact did this now defunct security measure have on the material experiences of users of these library spaces? How did it work, or did it work, in practical terms? How did the practice impact library use and users’ perceptions? For example, did the limitation on movement of materials encourage the development of scholarly communities and generate the basis for modern conceptions of the library as a place of study and contemplation? Do these security methods, now relics of the past and objects of curiosity, continue to influence reader’s experiences in libraries today? Unpacking all these and other questions completely is beyond the scope of this single assignment!

Today, modern libraries use more advanced technology, such as scanners, alarm systems, and surveillance cameras to prevent book theft and damage to collection materials. In the past, libraries relied upon chains, chests, locks and keys and curses (Kwakkel, 2015). Higgins concurs, writing,

“During the Middle Ages, monks and priests chained books to desks and shelves, and disseminated dire warnings detailing the horrible fate awaiting books thieves: Hanging, drowning, burning-or worse, all-condemning, generation inclusive curse (p.3).”

Early libraries depended on these methods because books were extremely valuable and vulnerable. Their value was based on the time and cost invested in their creation, and in their limited availability. Their vulnerability in times of great violence and upheaval is plainly evident, from the loss of the Great Library of Alexandria, to the traumas inflicted upon monasteries during the Reformation, to modern warfare and effects of natural disasters, such as floods and earthquakes.

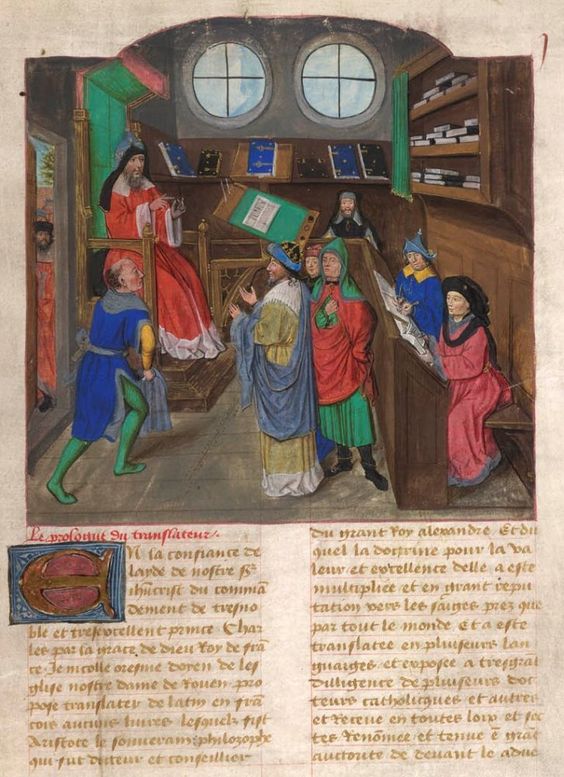

IN THE MIDDLE AGES, CREATING a book could take years. A scribe would bend over his copy table, illuminated only by natural light—candles were too big a risk to the books—and spend hours each day forming letters, by hand, careful never to make an error. To be a copyist, wrote one scribe, was painful: “It extinguishes the light from the eyes, it bends the back, it crushes the viscera and the ribs, it brings forth pain to the kidneys, and weariness to the whole body.” – Laskow

B.H. Streeter (1931), author of The Chained Library… famously wrote, “In the Middle Ages books were rare, and so was honesty. A book it was said, was worth as much as a farm; unlike a farm, it was portable property that could be easily purloined. Valuables in all ages require protection. Books, therefore, were kept under lock and key.” But, not only were books chained for their protection from theft, but the chaining occurred in exclusive environments, where rank or membership to an elite fraternity of scholars or monastic order determined who gained entrance to the library itself, whether it existed in a monastery or a university.

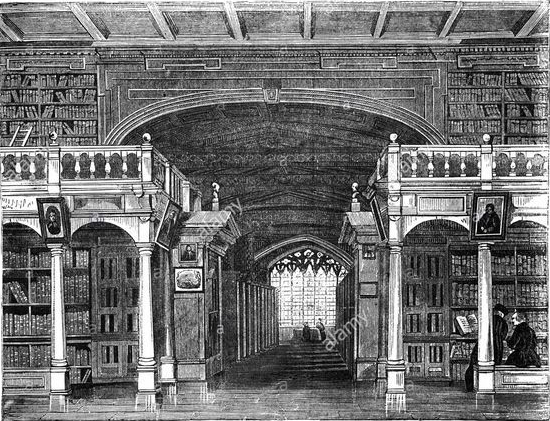

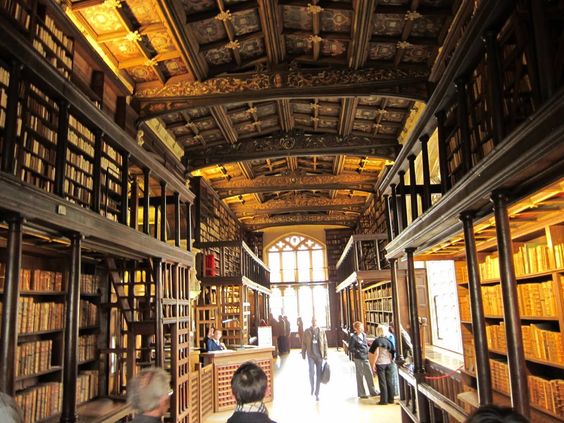

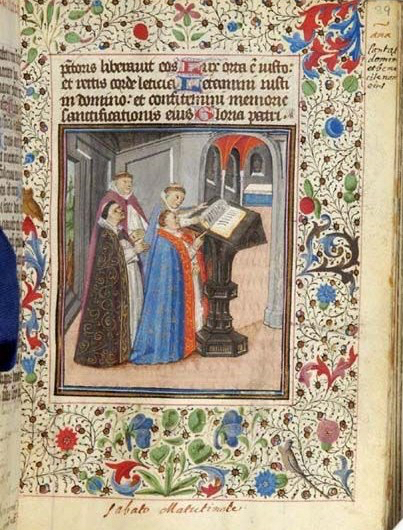

This frame of exclusive access need not be viewed only in negative terms; for example, for Sir Thomas Bodley, (as in The Bodliean Library, pictured above) viewed his role as that of a protector, not a hoarder. He sought to preserve, not prohibit learning. Summit writes that the Statutes of the Bodliean required, “to prevent by all good means, what here after may befall to the abusing, impairing or perhaps (which God forbid) to the utter subverting of our Store of Books (p.215). She writes that Francis Bacon, “praised Bodley for ‘having built an Ark to save learning from deluge’ (p.215).” Bodley’s views on the vulnerability of books were informed by his experience of the English Reformation, what Summit describes as”bibliographical trauma” in which monasteries were pillaged by the state and monastic libraries purged of Catholic learning. His determination to protect knowledge contained in books extended to Catholic writings and works that his King, James I, had banned, though he was not himself a Catholic.

Chained Libraries: Evolution

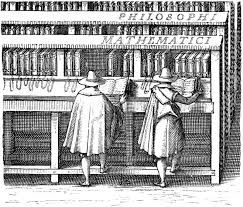

Colin Schultz, writing for Smithsonian.com in, “Libraries Used to Chain Their Books to Shelves, With the Spines Hidden Away” observes, “… in the long history of storing books, shelving the way we do is a relatively modern invention.” In the past, before books as we know them existed, tablets, then scrolls were used to record information, and were stored in a variety of ways. Books, shelving technology, and organization systems evolved over time. Mari, author of “Shelf-Conscious” notes,

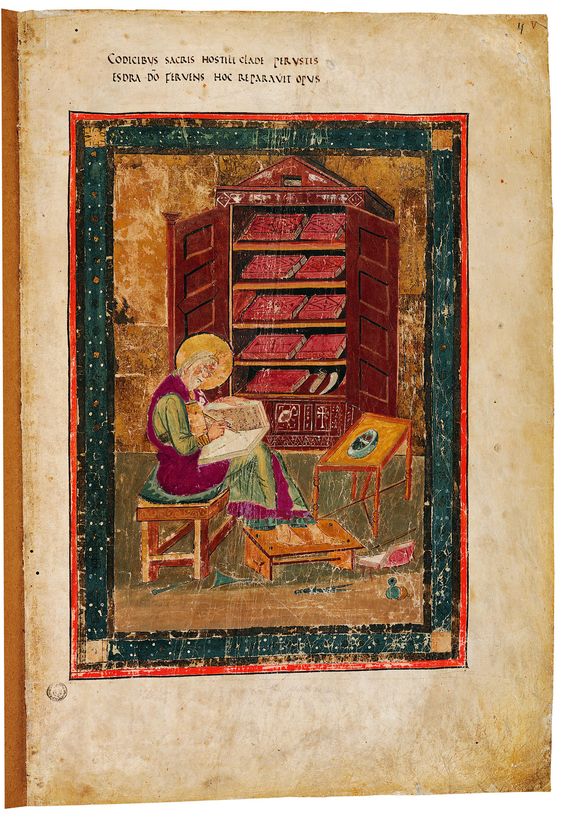

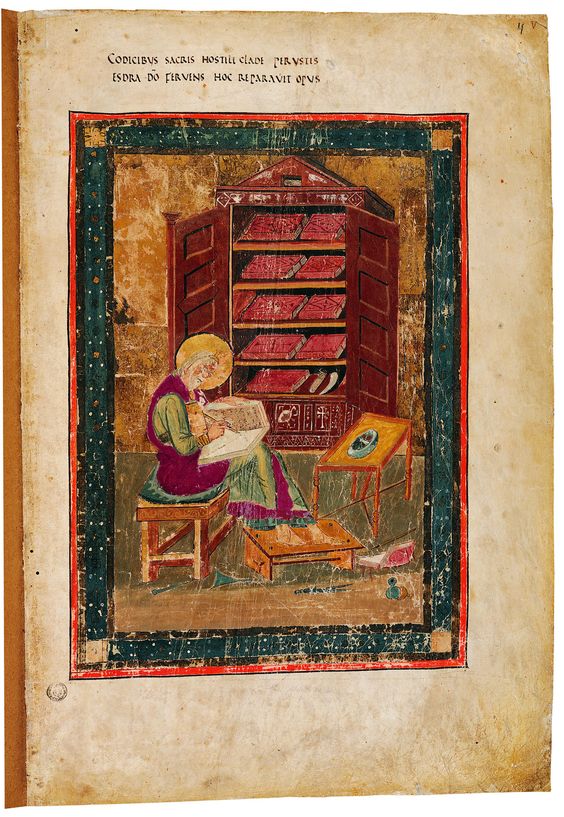

Armarium (book cupboard) Mauseoleum of Galla Placidia

Codex Amiatinus – British Library

“…around the time the codex emerged in the first century AD, open shelves—which now housed two clashing forms, the long cylindrical scroll and the flat rectangular codex—began to be considered hideous. Texts were sent into hiding, stored in armoires and trunks, which were convenient for transporting books, but not for accessing them. – Mari

Amaria (armarium) or scrinium, as described by Gameson were, “robust structure, raised up on four legs, and capped with a triangular pediment surmounted by a cross (p.33).” This type of library furniture is first depicted in a mosaic in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia at Ravenna”. He continues, “The paneled doors are open to reveal two shelves, each supporting a pair of hefty codices that lie flat on their back-boards, forages outward (p.33).” In 716 in England, a representation of an armarium is included in the Codex Amiatinus. With some changes, “it is essentially the same piece of furniture as that shown at Ravenna (p.33).” Later, shelves with doors that could be locked, and heavy chests with secure locks, evolved into other forms of library furniture such as lectern desks with benches attached to open shelves filled with chained books, which became, “standard library furniture int he late Middle Ages (Gameson, p.35).”

Dymphna Byre asserts that, “generally it was not until the mid-eighteenth century that chains went out of fashion.” Summit disagrees stating that, “chaining books did not end with the Middle Ages, but continued well through the early modern period, and in some cases, up to the nineteenth century. For example, Hereford, considered ’emblematic of monastic practice’ was not installed until the seventeenth century, following the example of the Bodliean (p. 236). For full and complete information on the history of chained libraries (357 pages long), see B.H. Streeter’s 1931 The Chained Library: A Survey of Four Centuries in the Evolution of the English Library.

How Spaces Impact Interactions

“Books and bookshelves are a technological system, each component of which influences how we view the other. Since we interact with books and bookshelves, we too become part of the system. This alters our view of it and its components and influences our very interaction with it. Such is the nature of technology and artifacts. (Petroski, p.1).”

If, as Petroski states, bookshelves are a sign of civilization and their very “presence…greatly influences our behavior (p.2)”, how did chained libraries impact the behaviors of users? For readers and the spaces occupied by chained libraries, their behaviors were determined and influenced by certain practicalities, for instance of light. If candles were prohibited to safeguard the books from the danger of fire, and books could not be moved due to chains, and the chains were attached to very heavy library furniture, the only source of light was natural- necessitating ample windows, and determining the placement of book tables and shelves, or lectern desks, near these windows. Petroski asserts,

“Chaining books impacts how the reader interacts with them, the space itself, as a window with natural light is the only source of light when candles are prohibited. The number of books in turn impacts how they are stored, when that number increases, putting pressure on the space, furniture and storage and users, who may now be crowded or forced to wait (p.2).”

Because particular works merited chaining, Byrne posits that, “The practice of reading and studying in the place where the books were kept evolved (p.5).” Perhaps this practice influenced the evolution of the utilitarian spaces of work into a place of contemplation and pleasant study?

Bringing books into one place also impacted behaviors of librarians, affecting what they collected and how they provided access to it while also keeping it secure from theft. According to Summit, “The consolidation of books collections into library rooms brought awareness of the limitations of space, forcing librarians to adopt a selective, rather than inclusive approach to library acquisitions (p.19).” Collection development also depended upon the whims and requirements of donors who placed conditions on their expensive donations so as not to be lost or damaged. Summits notes, “Donations required the ‘stipulation that they be ‘securely chained’ in communal collections. (p.235).

Chains themselves became synonymous and symbolic of another selective category: patrons and users. Summit notes what she calls the anti-fraternal critique of select townspeople who had some access to communally owned “so-called common-profit books”…which were, “circulated among readers in the fifteenth century” who viewed chained libraries negatively (p.18). These English critics found fault with monks, “whose books are ‘tyed up in cheines, and hidden under desk in the monks and fyrers libraries (p.235)”

Clearly the chains made a statement, an ideological statement according to medieval scholar Robert Rouse. Though discussing the use of the imagery of the chained library in Game of Thrones’ Citadel, his commentary on the control of knowledge and the maesters jealous control of it applies broadly to information in the modern world and the real medieval past. He says, “Information is power, and when you hold information you control the narrative” (Rothman, 2017).

“In response to…criticism, William Woodford, of the Oxford Greyfriars, defended the exclusivity of the fraternal libraries, explaining that the libraries had to guard books ‘in safekeeping so that they are not exposed to theft’: ‘For in some places where books have lain about in the open and secular clerks had free access to them, the books frequently have been stealthily removed, in spite of their being sturdily chained…So it behooved the friars to keep them locked up or they would have done without the books which they ought to study (Summit, p.18).”

Chained libraries faced criticism not only for exclusivity but for practical reasons as well. With increased access so does risk to materials increase (Shuman, p.2) requiring chains on books which then creates “problems of management and convenience (Petroski, p.2). On the topic of practical concerns of convenience Mari observes, “The problem, of course, was that two books chained next to each another couldn’t be comfortably studied at the same time: elbows knocked; shackles clinked and tangled.” Byrne agrees, noting, “students were queuing three or four deep to use the books chained to the lecterns.”

Conclusion

Since the beginning of time libraries have faced issues of security. Threats from fire, theft, vandalism and social upheaval have been a constant. Solutions to these issues have included locked chests, supernatural curses on thieves and vandals of books, and chains. The chains method can be perceived as both a more effective security measure than curses that appears restrictive to both modern eyes and medieval users, but must also be considered as a facilitator of access. Chains were also a statement of values regarding books, which were expensive and symbols of both power and learning, and as communal and exclusive property. Library furniture, from armaria, to book chests, to lecture desks with chained shelved books historically has been designed with three aims in mind: access, storage and preservation. These physical and spacial realities have in turn impacted how users in the past and present interact with libraries and books and how library professionals maintain the library itself and facilitate access.

“Librarians have had to be concerned with theft since libraries first came into existence, thousands of years ago. The medieval chains dangling from handwritten codices and incunabula at the Bodleian Library of Oxford University, England, and elsewhere, while keeping books on their shelves, attest silently to this simple truth. Monastic and civil librarians have always attempted to foil crooks. Only today’s methods differ from those of centuries ago; their aim has not changed at all. Wherever there have been collections of important books or other materials-things worth holding onto-there have been book thieves and mutilators of library materials (Shuman, p.8).”

For more fun with chained libraries, please check out my Pinterest board on the topic of book shelving history: Shelf-Conscious.

To learn more about one of the most famous remaining chained libraries, read and watch a video from this BBC. com piece on Hereford.

References

BBC.com. (2018). The ancient library where the books are under lock and key.

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20180706-the-ancient-library-where-the-books-are-

under-lock-and-key

Book Addiction. (2016). Shelving books the old-fashioned way.

https://bookaddictionuk.wordpress.com/2016/03/20/shelving-books-the-old-fashioned-

way/

Hereford Cathedral (n.d.) Chained Library. https://www.herefordcathedral.org/chained-

library

Higgins, S. (2015). Theft and vandalism of books, manuscripts, and related materials in

public and academic libraries, archives, and special collections. Library Philosophy and

Practice(e-journal.) 1256. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1256/

Kwakkel, E. Chain, chest, curse: Combating book theft in medieval times.

https://medievalbooks.nl/tag/book-theft/?blogsub=confirmed#blog_subscription-5

Laskow, S. (2016). Protecting your library the medieval way, with horrifying book curses.

Atlas Obscura. November 9, 2016. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/protect-your-

library-the-medieval-way-with-horrifying-book-curses?

utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=atlas-page

Mari, F. (2012). Shelf-Conscious. The Paris Review. December 27, 2012.

Petroski, H. (1999). The book on the bookshelf. New York: Alfred A. Knoph.

Rothman, L. (2017). “Game of Thrones made it abundantly clear why real medieval

libraries chained their books.” Time. July 17, 2017. http://time.com/4861039/game-of-

thrones-oldtown-library/

Schultz, C. (2013). Libraries used to chain their books to shelves, with the spines hidden

away. Smithsonian.Com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/libraries-used-

to-chain-their-books-to-shelves-with-the-spines-hidden-away-4392158/

Shuman, B. (1999). Library security and safety handbook: Prevention, policies and

procedures. Chicago: American Library Association.

Streeter, B.H. (1931). The chained library: A survey of four centuries in the evolution of the

English library. London: Macmillian and Co., Limited.

Summit, J. (2008). Memory’s library: Medieval books in early modern England. Retrieved

from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu