(This post is comprised of the original blog post with additional research and historical information added for context.)

The Indiana Colonization Society, formed 1829 and based in Indianapolis, advocated for the relocation of free people of color and emancipated slaves in Indiana to settlements in Liberia, Africa. The ICS was an auxiliary of the American Colonization Society (located in Washington D.C.) which formed in 1817. Indiana University offers an excellent guide to resources both online and in print on this topic.

Premised on the idea that an integrated society was impractical and impossible, “Colonizationists” (overwhelmingly white) argued that black people could find liberty only in Africa. Some free people of color (a small number) who agreed that justice, liberty and prosperity could not be achieved in America emigrated. Critics -such as free black people and abolitionists -voiced strong opposition to this movement. They asserted that the agenda of the society was counterproductive for racial reconciliation and integration, that it was overall an ineffective scheme to combat slavery and finally that it undermined anti-slavery efforts. According to Anthrop writing in the Indiana Historian (2000), free people of color who wished to “fight against slavery and for equal rights as American citizens” viewed this plan as effectively abandoning those still enslaved (p.6). “Abolitionists saw the colonization movement as a slaveholders’ plot to safeguard the institution of slavery by ridding the country of free blacks” (Anthrop, p.6). Colonizationists maintained that their motives were benevolent and philanthropic, but even supporters questioned whether the idea of relocation was even practically feasible or financially realistic.

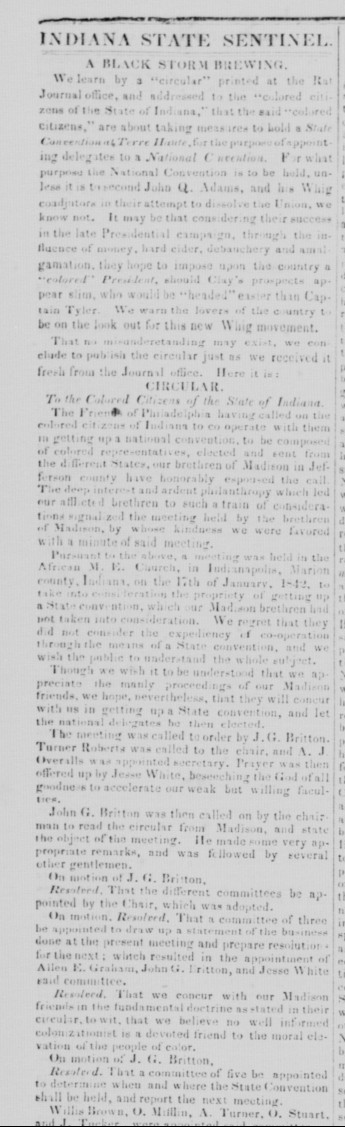

In the 1820’s and 1830’s, the movement gained support in the state legislature and with citizens throughout the state, but by late 1830’s interest and activity declined (Antrhop, p.7). Black Hoosiers opposed it vehemently, resolving at an 1842 convention that, “we believe no well-informed colonizationist is a devoted friend to the moral elevation of the people of color.”

Indiana State Sentinel, Volume 1, Number 36,Indianapolis, Marion County, 1 March 1842 |

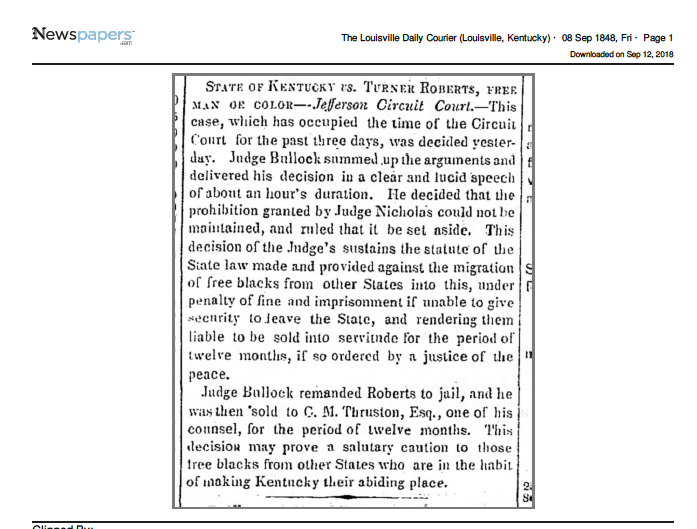

“Turner Roberts was called to the chair,” according to the 1842 Indiana State Sentinel story. Rev. Turner W. Roberts (1808 – sometime after 1867), was a free man of color, born in North Carolina between 1808 and 1813. In 1848, he travelled to Louisville Kentucky and remained there over thirty days, violating the Commonwealth’s statute against free people of color emigrating and residing in Kentucky. He was arrested and charged with breaking the law, which he then challenged in court. The state found that he was not a “citizen” and that he must pay the fine or be sold into servitude for 12 months. He was “purchased” by his attorney. His case was publicized by Frederick Douglass’ North Star. He also worked as a barber and resided in Indianapolis as late as 1867.

“Reverend Turner Roberts was an early challenger to Kentucky laws against free African Americans migrating to Kentucky.” – Notable Kentucky African Americans Database.

The ICS reacted to this criticism and push back with renewed efforts for the movement when in 1845 Rev. Benjamin Taylor Kavanaugh was named as its agent. He was tasked with raising awareness, organizing supporters and local auxiliaries, fundraising and emigrant recruitment (Anthrop, p.8).

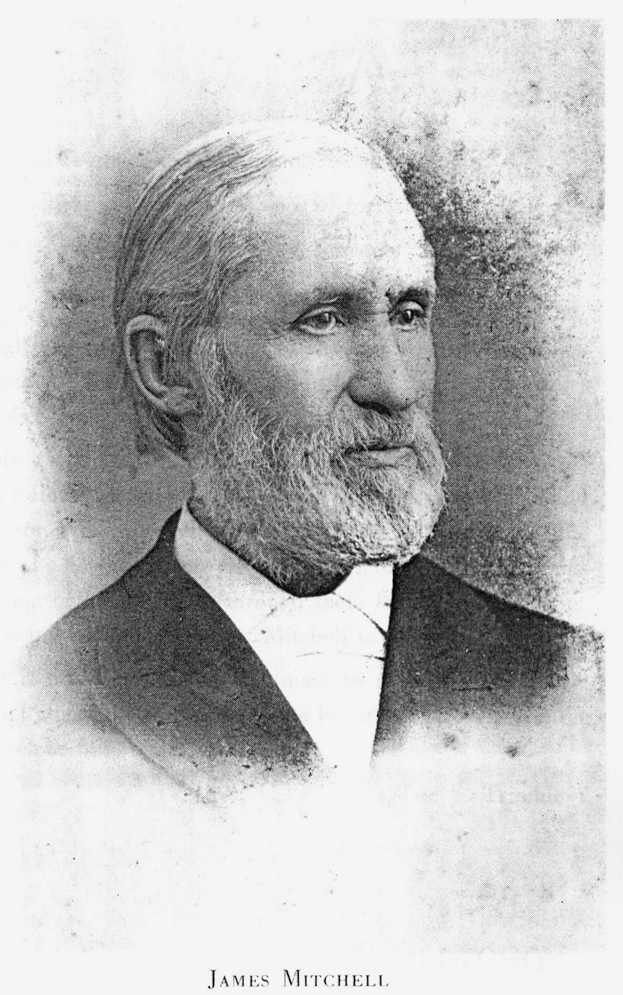

By 1848, the Rev. James Mitchel (1818-1903), a Methodist minister, abolitionist, and colonization advocate, took over as agent and Secretary of the American Colonization Society of Indiana. Both Kavanaugh and Mitchell recruited black ministers to raise awareness in the black community and to identify potential emigrants. These men, Rev. John McKay and Rev. Willis R. Revels, had limited success. “Revels won approval from black citizens…but soon gave up his post.”

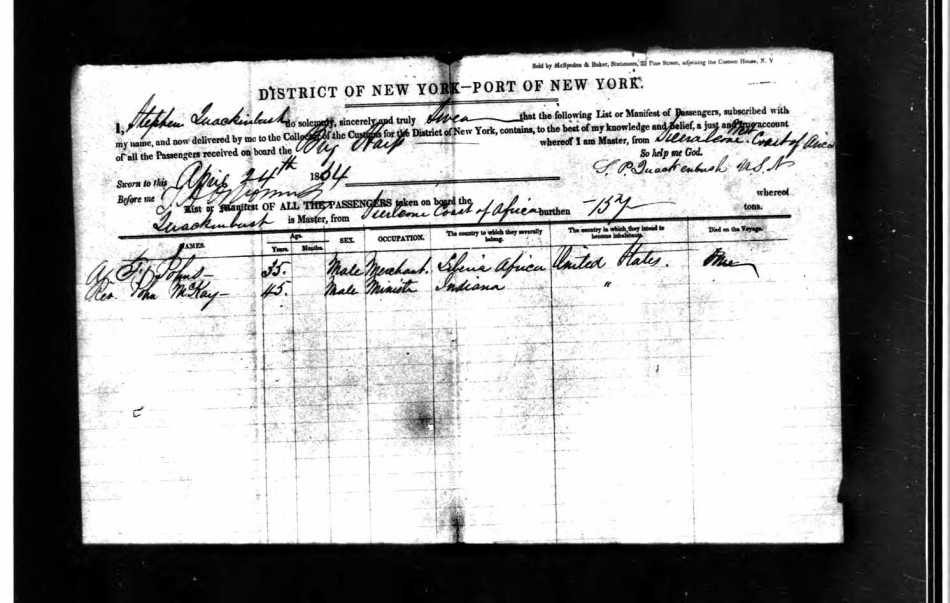

Kavanaugh attributed this to pressure from abolitionists (Anthrop, p.8). McKay, was appointed as, “an agent for the board to purchase land in Liberia and promote colonization among Indiana black citizens” (Antrhop, p.9). In the 1850’s he traveled to Liberia with two groups of emigrants and observed the colony, reporting back enthusiastically.

Escalating tension between the north and south over slavery, and increasing violence over issues such as the question over expansion of slavery into new territories led to laws in Indiana that gave free people of color reason to consider emigration, even if the vast majority chose to remain in the country of their birth. During the period of the 1830s until the 1850’s, according to Anthrop, “increasing tensions nationally between antislavery and slavery factions…resulted in increasing prejudice against blacks. The culmination of this prejudice in Indiana was Article XIII of the Indiana Constitution of 1851”, which prohibited blacks and mulattoes to enter or settle in the state. Fines set for violation were appropriated to “defray costs of sending blacks in Indiana to Liberia.” Further legislation, “required all blacks already living in Indiana to register with the clerk of the circuit court” (Anthrop, p.4).

In 1852 ICS advocacy led to a state initiative when the Indiana General Assembly formed the Indiana Colonization Board and began providing funds to help, “Indiana free blacks emigrate to Liberia on the western coast of Africa” (Anthrop, p.2). The state government appropriated funds to finance the purchase of land in Liberia and for the transport and support of immigrants. According to Anthrop, “eighty-three” free people of color emigrated from Indiana to Liberia, but, the state board facilitated the departure of “only forty- seven” of those emigrants. During the 1840’s, 1850’s and 1860’s advocates and critics within the movement and the government squabbled over complaints about financial arrangements, funding cuts, fundraising methods, settlement location and administration and over negotiations with the government of Liberia. James Mitchell, in an 1855 “Circular to the Friends of African Colonization” apprising society members of the progress and obstacles faced by the movement, admitted the paltry sum of $65 per person for emigration was insufficient to provide for transportation, and offered nothing for support or protection of immigrants. In the final report in 1863 to the State Board by its secretary, the author, William Wick, concluded that the movement had been a “total failure.” Wick attributed this failure to the ambition of formerly enslaved people to be equal in social status to white Americans.

To explore primary sources on this topic available at the Indiana State Library Digital Collections, use these subject terms or click on the subject terms links below:

African Americans–History

African Americans–Indiana

Indiana–History

Colonization

African Americans–Social conditions

Grand Cape Mount County (Liberia)

Liberia

Back to Africa movement

Emigration and immigration

Indiana State Board of Colonization

Indiana Colonization Society

The types of records in the Indiana Digital Collections sub collection of the Colonization Movement include government documents, such as the report to the State Board of Colonization, organization records, such as Indiana Colonization Society reports, Circulars that act as newsletters to supporters, private society correspondence disseminated to influential political operatives and the society’s monthly publication The Colonizationist, as well as a campaign literature from the 1860 race for the governorship of Indiana in a the form of speech by Oliver P. Morton. These materials offer insight into the theoretical and philosophical tenets of the Colonization Movement, document its efforts, successes and obstacles, provide historical context and can be used to map out its historical trajectory from a burgeoning movement to abject failure. Scholars and students will find these items to be a rich resource for exploring the history of the Back to Africa movement. Genealogists and historians will find in these primary sources a wealthy of information on the individuals active in this movement, and on those who ultimately emigrated to Liberia.

Colonizationist May 1847, vol. 2, no.2

Twelfth Annual Report of the Indiana Colonization Society, 1847

Circular to the Friends of African Colonization

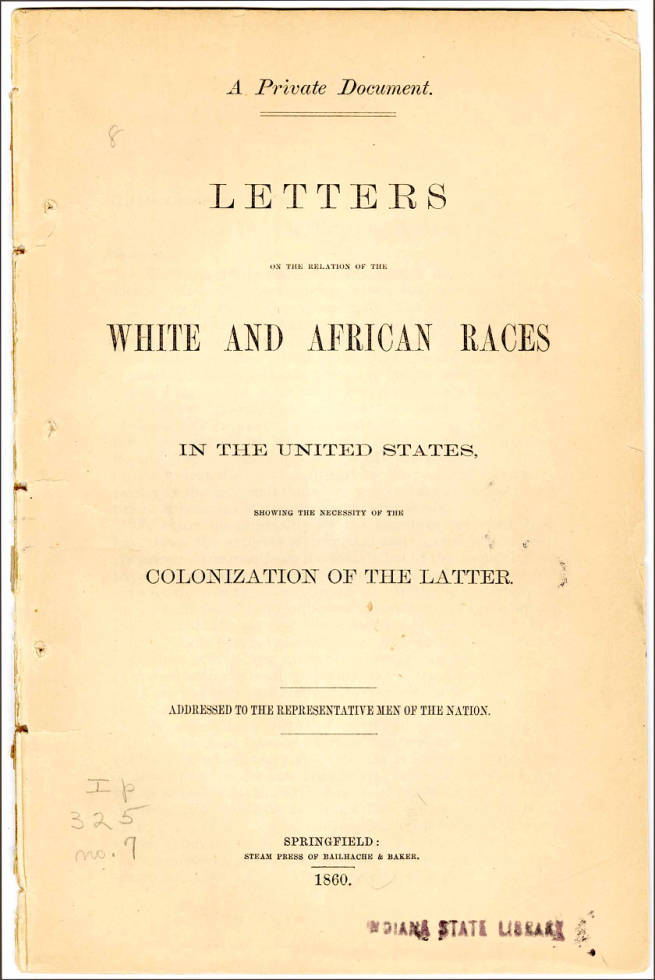

ISL_IND_PAM_LtrsColMov1860

This pamphlet is a collection of private letters written by James Mitchell as agent of the Indiana Colonization Society, on the subject of the African Colonization Movement, detailing the actions, policies and theoretical foundation of the organization. It is addressed to the candidates for the 1860 U.S. Presidential election. Mitchell seeks to privately communicate the aims of the movement to popular leaders and the future president. The correspondence includes an extract from the report to the legislature of the state of Indiana (1852) titled, “The Separation of the Races Just and Politic”, an 1857 letter from Mitchell to President James Buchanan, and an 1849 letter to President Zachary Taylor.

The Speech of Oliver P. Morton, the Republican candidate for Lieutenant Governor, 1860

Report on colonization for 1863 to the state board

References and Other Resources

Anthrop, M. (March 2000). Indiana emigrants to Liberia. The Indiana Historian, March 2000. Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.in.gov/history/files/inemigrants.pdf.

American Colonization Society Collection at the Library of Congress, Finding Aid

American Colonization Society Collection

American Colonization Society records, 1792-1964

“Did Lincoln Want to Ship Black People Back to Africa?” – Henry Louis Gates, The Root